Land Evaluation: How to Evaluate Land [with schematic representation]!

The FAO Framework for Land Evaluation:

The Framework for Land Evaluation sets out basic concepts, principles, and procedures for land evaluation that are “universally valid, applicable in any part of the world and at any level, from global to single farm.” The universal validity means its potential for application across disciplinary boundaries.

The Framework has been followed by a series of guidelines for rain fed agriculture, forestry, and irrigated agriculture. These guidelines provide an expansion of the basic concepts and details on the operational aspects of the procedures recommended in the Framework.

The Framework as such does not constitute an evaluation system but is primarily designed to provide tools for the construction of local, national, or regional evaluation systems in support of land use planning. The two basic means to achieve this goal are land improvement and land management improvement.

Land Suitability Categories According to FAO Framework for Land Evaluation:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

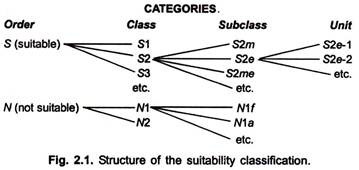

Land Suitability is described by a hierarchical system of classification-

Land Suitability Orders:

Order S – suitable land (current or potential, according to requirements)

This land is expected to yield benefits that justify the costs (without unacceptable risk of damage to land resources).

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Order N – not suitable land

This land is not expected to yield benefits justifying the costs, or would entail unacceptable risks of damage to land resources, or both.

Land may be classed as ‘Not Suitable’ for a given use for a number of reasons. It may be that the proposed use is technically impracticable, such as the irrigation of rocky steep land, or that it would cause severe environmental degradation, such as the cultivation of steep slopes. Frequently, however, the reasons are generally economic – the value of the expected benefits does not justify the expected costs of the inputs required.

Land Suitability Classes:

Land suitability classes reflect degrees of suitability. The classes are numbered consecutively, by Arabic numbers, in sequence of decreasing degrees of suitability within the order. Within the order ‘Suitable’ the number of classes is not specified. There might, for example – be only two, S1 and S2. The number of classes recognized should be kept to the minimum necessary to meet interpretative aims; five should probably be the maximum.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

If three Classes are recognized within the order ‘Suitable’, as can often be recommended, the following names and definitions may be appropriate in a qualitative classification:

1. Class S1-Highly Suitable:

Land having no significant limitations to sustained application of a given use, or only minor limitations that will not significantly reduce productivity or benefits and will not raise inputs above an acceptable level.

2. Class S2-Moderately Suitable:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Land having limitations which in aggregate are moderately severe for sustained application of a given use; the limitations will reduce productivity or benefits and increase required inputs to the extent that the over-all advantage to be gained from the use, although still attractive, will be appreciably inferior to that expected on Class S1 land.

3. Class S3-Marginally Suitable:

Land having limitations which in aggregate are severe for sustained application of a given use and will so reduce productivity or benefits, or increase required inputs, that this expenditure will be only marginally justified.

Structure of the Suitability Classification:

The structure of the suitability classification, together with the symbols used, is summarized in Fig. 2.1. Depending on the purpose, scale and intensity of the study, either the full range of suitability orders, classes, subclasses and units may be distinguished, or the classification may be restricted to the higher two or three categories.

Within the order ‘Not Suitable’ there are normally two classes:

1. Class N1:

Currently not suitable.

Land for which the proposed use is physically possible, but under present conditions fails to yield benefits justifying the costs of the required major land improvement measures. The chances of currently not suitable land being converted into suitable land are remote.

Example 1:

Food crop production on remote land of low chemical fertility but with good physical properties in a land-locked country with few and long lines of transport. The establishment of a local fertilizer plant would change this situation. This example is a clear-cut case of land improvement (infrastructure) being a prerequisite to soil improvement (chemical fertility).

2. Class N2:

Permanently not suitable.

Land for which the proposed use is expected to be physically impracticable within the foreseeable future.

Example 2:

Strongly sloping land with shallow soils classified with a view to mechanized food crop production (land use type).

The class criteria for currently not suitable land may vary with time, according to possible changes in economic conditions and technological developments and, consequently, is less rigid than the physical class criteria of permanently not suitable land.

The differences in degrees of suitability are determined mainly by the relationship between benefits and inputs. The benefits may consist of goods, e.g. crops, livestock products or timber. The inputs needed to obtain such benefits comprise such things as capital investment, labour, fertilizers and power.

Thus an area of land might be classed as Highly Suitable for rain fed agriculture, because the value of crops produced substantially exceeds the costs of farming, but only Marginally Suitable for forestry, on grounds that the value of timber only slightly exceeds the costs obtaining it.

A land suitability classification that only considers the physical land attributes (of which soil, topography and drainage are of primary importance) is referred to as a Physical Land Suitability Classification. If the land suitability classification system considers both the physical and relevant, socio-economic factors it is referred to as an Integral Land Suitability Classification.

Land Suitability classes in economic terms do not necessarily coincide fully with the physical land suitability classes. The latter classes, however, do support the determination of suitability classes in economic terms by providing essential data on technical input coefficients as well as on returns to be expected.

Land Suitability Subclasses:

Land suitability subclasses are made to show the land qualities that act as limitations. The reasons for placing areas in a lower class than Class S1 is indicated by appending lower-case letters with mnemonic significance to the class symbols to show the nature of the land qualities that act as limitations.

The number of subclasses should be kept to the minimum that will satisfactorily distinguish lands that are expected to differ significantly in their management and improvement requirements. As few limitations as possible should be used for each subclass symbol.

Land within the order ‘not suitable’ may be divided into subclasses according to the kinds of limitations, although this is not essential.

Other groupings of land qualities can be made in relation to other uses of the land, for example recreation, wild life, nature conservation.

The more specific the type of land use, the more specific the relevant land qualities. Especially, when assessing the improvement capacity of a specific land quality, its single components should be quantitatively recorded and analysed.

Land Suitability Units:

Suitability units within the same subclass differ from each other in production characteristics or in minor aspects of their management or improvement requirements (often definable as differences in detail of their limitations). Their recognition permits detailed interpretation at the farm-planning level.

Example – Differences in the required density of the drainage network to meet the drainage requirements of the defined type of land use, differences in soil conservation measures, etc.

Land Quality:

The FAO Framework recommends describing the land in terms of land qualities. The basic land data in terms of land characteristics is converted to specific land qualities. Land qualities are rated on a scale ranging from 1 (very good) to 5 (very poor). These ratings are compared with the requirements of a given land use. Similar listing can be made for irrigated agriculture.

The procedures involved in land evaluation broadly are:

I. Preparation,

II. Field-work,

III. Evaluation and

IV. Presentation.

I. Preparation comprises of:

1. The establishment of the objectives of the evaluation, the proposed changes in land use, and the data and assumptions on which the evaluation is to be based; and

2. The specification of the area to be studied and its accessibility, the relevant types of land use and their requirements, the type of suitability classification to be employed, and the survey intensity and the scale(s) of the map(s) to be published.

II. Field-work comprises of:

1. Delineation of mapping units;

2. Checking of land use requirements;

3. Establishment of land qualities, and limitations by comparing requirements with qualities; and

4. Inventory of the present economic and social conditions.

III. Evaluation comprises of:

1. Elaboration of the land suitability classification;

2. A field checks of the evaluation;

3. Formulation of required land improvement(s);

4. Estimation of costs and benefits;

5. Economic and sociologic analysis; and

6. Assessment of the impact of the proposed measures on the environment.

IV. Presentation comprises of the drawing up of the report and map(s).

A schematic representation of activities in land evaluation is given in Fig. 2.2.